Today is the 555th anniversary of Mehmet the Conqueror's taking of Istanbul from the Byzantines (you may have gathered this from the title) and the Turks are celebrating in pretty spectacular style.

That's Yeni Cami (New Mosque). The banner says "conquered for 555 years" or some such. There were purportedly fireworks somewhere over the Golden Horn but I didn't get any pictures of them.

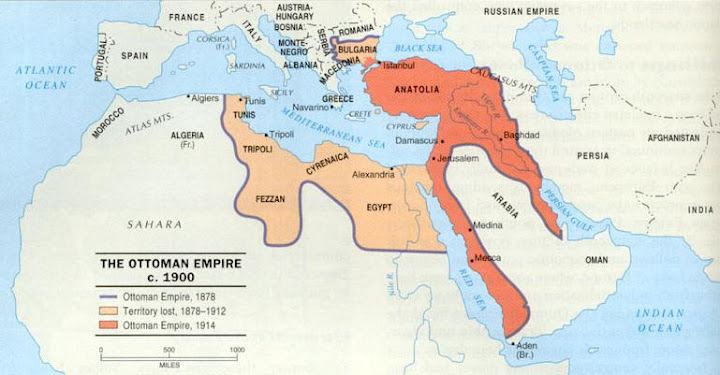

Clayton was very surprised that Turkey was celebrating the conquest with so much pomp given their attempts from Ataturk onwards to downplay past hostility towards the West and their recent push to join the EU. It is pretty surprising, really. This spring I was trying to decide whether or not I wanted to participate in a program that focused as much on history as this one does. Dr. Shields argued that the Byzantine and earlier history of Anatolia is vital to one's understanding of modern Turkey because the Republic has tried to tie more into this heritage than the militant Islamic character of the Ottoman period.

Wellllll... maybe. I mean, this is a pretty explicit tie to those militant Islamic Ottomans right here.

Earlier today one of the Sabancı students told me that they take 8 years of Turkish history in school. That's pretty significant compared to the year students get in the U.S. (though, granted, there's a lot more Turkish history to cover). So even though the Republic is trying to move relentlessly forward, they're spending an awful lot of their time looking backward to remember all the cool stuff they've done in the last 1000 years. As deplorable as the average U.S. student's grasp of our history is, celebrating military victories from 500 years ago seems a bit excessive. How healthy is it for a country to keep looking forward and backward at the same time?

Clayton was very surprised that Turkey was celebrating the conquest with so much pomp given their attempts from Ataturk onwards to downplay past hostility towards the West and their recent push to join the EU. It is pretty surprising, really. This spring I was trying to decide whether or not I wanted to participate in a program that focused as much on history as this one does. Dr. Shields argued that the Byzantine and earlier history of Anatolia is vital to one's understanding of modern Turkey because the Republic has tried to tie more into this heritage than the militant Islamic character of the Ottoman period.

Wellllll... maybe. I mean, this is a pretty explicit tie to those militant Islamic Ottomans right here.

Earlier today one of the Sabancı students told me that they take 8 years of Turkish history in school. That's pretty significant compared to the year students get in the U.S. (though, granted, there's a lot more Turkish history to cover). So even though the Republic is trying to move relentlessly forward, they're spending an awful lot of their time looking backward to remember all the cool stuff they've done in the last 1000 years. As deplorable as the average U.S. student's grasp of our history is, celebrating military victories from 500 years ago seems a bit excessive. How healthy is it for a country to keep looking forward and backward at the same time?