We went to the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations this afternoon. Our guide, a history professor from the local Bilkent University, prefaced the tour of the museum by telling us that Turks had thought their history began with the Ottoman Empire until Ataturk revealed that Anatolian history stretched back to the beginning of history. Thank God for Ataturk.

Turkish identity began in 8000 BC and has been going strong ever since through the empires of the Hatis, Hittites, Phrygians, Lydians, Greeks, etc. Of course none of these groups were actually native to Anatolia Ataturk defined the Turkish ethnicity as anyone living in Anatolia, and apparently this was applied retroactively as well.

What's that carved on that dagger? Could it be... a crescent?! Do you think it's a coincidence that the Hittites made a dagger with a crescent? Of course not! They were loyal Turks eagerly anticipating the establishment of the Republic some 4000 years later.

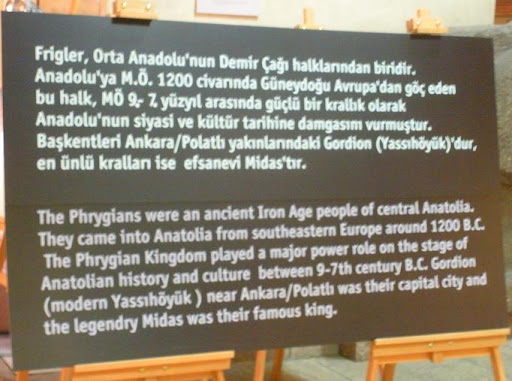

Of course I'd be remiss in my description of Turkish heritage if I didn't mention the Phrygian king Midas (yes, the Midas), who many people wish was buried near the sight of Gordion, which is in turn near Ankara (but he's probably not). Midas is yet another bit of Turkish heritage that had little to do with the Anatolians of antiquity and has less to do with Turkey today. But damn it all, he lived and died in Anatolia, so he's a Turk.

The museum is very excited to have such a personage as Midas in Turkey. At times they control their glee.

And at times they don't.

They're not alone in being excited about this. When we went to visit Gordion and Midas ourselves I learned that part of the compulsory military service Turkish men undergo is a quick 'cultural appreciation' tour of the country so they learn just what they're fighting for. One of the major stops on that tour is Midas' tomb, which I'm sure really helps to stiffen their resolve to never surrender an inch of their homeland.

At some times the layers of identity are pretty obvious.

Layer of Identity 1 would be the original Ankara Castle, which was built by the Byzantines out of whatever materials were readily available (this includes columns, etc. from the Greeks... let's call them Layer of Identity .5). More recent layers of identity were made of brick (patriotically red brick, you'll note) and a stucco clocktower that could be found anywhere in Europe.

But the assimilation of so many cultures that weren't really meant to be assimilated into Turkish identity hasn't always been easy. Often Turkey has had to turn those cultures, and history itself, upside down to make it all fit together.

Ha! Upside down! Man, I kill myself sometimes.

In all seriousness Ankara really is a fantastic place to see the contrast of Old and New Turkey and get a feel for all the layers of identity that have been pressed together to create Turkish identity. On the hill surrounding Ankara Castle you can see what is very nearly the original village of Ankara that existed before 1922.

Stretching out around the castle, though, is Republican Ankara, a testament to 90 years of rapid growth and modernization.

Whoever said Ankara was a boring city was patently wrong. Istanbul is a beautiful blend of old and new. Ankara has that same old and new, but the line between the two is much more stark.

That is old Ankara.

This is new Ankara.

That is old Turkey.

This is new Turkey.

Maybe these things make it a bad place to live - maybe having to choose between old and new Turkey keeps you from experiencing the full flavor of the other. But boring it is not.

Of course I'd be remiss in my description of Turkish heritage if I didn't mention the Phrygian king Midas (yes, the Midas), who many people wish was buried near the sight of Gordion, which is in turn near Ankara (but he's probably not). Midas is yet another bit of Turkish heritage that had little to do with the Anatolians of antiquity and has less to do with Turkey today. But damn it all, he lived and died in Anatolia, so he's a Turk.

The museum is very excited to have such a personage as Midas in Turkey. At times they control their glee.

And at times they don't.

They're not alone in being excited about this. When we went to visit Gordion and Midas ourselves I learned that part of the compulsory military service Turkish men undergo is a quick 'cultural appreciation' tour of the country so they learn just what they're fighting for. One of the major stops on that tour is Midas' tomb, which I'm sure really helps to stiffen their resolve to never surrender an inch of their homeland.

Boys, those barbarous Greeks are coming a-raping and a-pillaging yet again and we have to hold them here. I won't tell you to think of your sisters, who will be despoiled by their priests and left for dead. I won't tell you to think of your homes, which will be burned down and demolished by those Orthodox dogs. I want you to think about Midas, a good man and a good Turk who fought and died for this country some 3000 years ago. Do you want some Greek taking pictures of his tumulus? Buying postcards at his souvenir shop? Do you?Actually, Turks take their Anatolian history very seriously across the board. The museum is one of the major pit stops for Turkish children who come into Ankara from eastern Anatolia for their first dose of TURKISHNESS. At some level it's admirable what Turkey's done with its history. It has this incredible smörgåsbord of cultures that have somehow been blended into a tapestry of identity that, factual and accurate or not, certainly makes for a good story.

At some times the layers of identity are pretty obvious.

Layer of Identity 1 would be the original Ankara Castle, which was built by the Byzantines out of whatever materials were readily available (this includes columns, etc. from the Greeks... let's call them Layer of Identity .5). More recent layers of identity were made of brick (patriotically red brick, you'll note) and a stucco clocktower that could be found anywhere in Europe.

But the assimilation of so many cultures that weren't really meant to be assimilated into Turkish identity hasn't always been easy. Often Turkey has had to turn those cultures, and history itself, upside down to make it all fit together.

Ha! Upside down! Man, I kill myself sometimes.

In all seriousness Ankara really is a fantastic place to see the contrast of Old and New Turkey and get a feel for all the layers of identity that have been pressed together to create Turkish identity. On the hill surrounding Ankara Castle you can see what is very nearly the original village of Ankara that existed before 1922.

Stretching out around the castle, though, is Republican Ankara, a testament to 90 years of rapid growth and modernization.

Whoever said Ankara was a boring city was patently wrong. Istanbul is a beautiful blend of old and new. Ankara has that same old and new, but the line between the two is much more stark.

That is old Ankara.

This is new Ankara.

That is old Turkey.

This is new Turkey.

Maybe these things make it a bad place to live - maybe having to choose between old and new Turkey keeps you from experiencing the full flavor of the other. But boring it is not.